It’s mid-morning in Singapore and already the air is throttled with suffocating heat. Just around the corner from the bustle of Orchard Road is a school, its sprawling campus an oasis from the frenzy of the city. Today, school is not in session. The campus is muted, with only the rustling of towering palm fronds mingling with the metallic cries of cicadas. Venture a little further here, and you come upon an auditorium, its doors firmly shut to the outside world.

Inside, under the white glare of fluorescent lights, a few hundred heads are dipped low in concentration in a sea desks. We are all young – twelve-years-old or so – our eyes on the test paper before each of us. None of us are local to Singapore, and the campus, too, is entirely foreign. As strangers, we are united today for one thing only: the gruelling entrance exam for foreigners to the top-ranked secondary school in Singapore.

Soon, it’s all over. Papers are collected and stacked at the front, the double doors of the auditorium swing open, and a wave of tropical heat rush at us as we’re released back out into the world.

I find my parents amidst the crowd and we make for the school gates. Just before we leave, I pause to take in the beautiful campus behind me one more time.

I didn’t know it then, but my life was about to change – dramatically. In time, the good news would trickle in: first, an invitation to meet with the vice-principal; then, a letter bearing an invitation to matriculate. This was how, at age 13, I left my family and our expat life in Guangzhou, China and moved to attend a local school in Singapore. For the next 6 years, I lived there with a guardian and charted my own path through adolescence.

What followed could only be described as A Very Good Life: after secondary school, I went on to a scholarship class at the top high school in the nation. This local school has the added distinction of being one of the top 5 schools in the world for the most offers received for further studies at Oxford and Cambridge, beating out the likes of Eton and Harrow.

Surrounded by incredible teachers and peers, propelled by a world class education, I would learn at a ferocious pace, enjoying debates about Keynesian economics and Seamus Heaney between classes (that is, when my friends and I weren’t breaking school rules playing bridge and occasionally serving detention for our sins).

I would go on to forge lifelong friendships and grow in other ways – competing at the national level in chess and karate, clinch national titles, receive invitations to join the national team in both disciplines (then having to decline because, well, I wasn’t Singaporean).

I would serve in several leadership positions, win intramural awards, enter an incredible Ivy League university and make Dean’s List every semester (barring that first year; goodness, that first year was an adjustment). After graduating I’d go on to a decade of working in the heady world of finance before becoming an artist whose paintings have since been exhibited in London, New York, and Shanghai and have found homes in private art collections around the world. Then, one day, when I was least expecting it, I met the love of my life and the rest is history.

This all sounds pretty nice, right? Yet to conclude that this is a typical outcome for TCKs would be a gross error, for the truth is quite often the opposite.

A Tale of Two Outcomes

Online, across the many platforms where TCKs congregate, a darker picture of what it means to be a TCK emerges. Over and over, cries for help fill the screen. Here’s a small but representative sample of what fellow TCKs have shared and kindly agreed to have republished, a glimpse into the common struggles that non-TCKs rarely see:

“I don’t have any friends. I don’t speak my native language at a native level, I don’t feel like I belong anywhere…. I feel like my youth passed by in front of my face while I missed all the experiences and moments with the friends I had back what once was my home. Here I feel like I’m incarcerated, in a prison.”

“What’s the point of living if everyone surrounding you doesn’t understand you and the people closest to you are in another country and have already moved on?”

“I’m 38 and as the days go by, I’m realising how badly the TCK life affected me more clearly everyday. It is a lifestyle with a HUGE dose of toxicity on the psyche. HUGE.”

“I spent a year with psychedelic plant medicines to help my desolation with ‘not belonging anywhere’. Sometimes I like to imagine the vines of a banyan tree reaching into my heart, wrapping themselves around it, and saying, ‘You belong right here, right here with the earth.’”

“I just moved to the US after 18 years living between Africa and Asia. It’s been about two months, and it’s finally hit me that I don’t have a return ticket to either of those continents. I’m trying to process my emotions and events bit by bit. I’m trying to journal daily and will see a therapist every other week. But it still hurts so damn much. I’m crying several times a day. It hits me when I’m in class, tearing up during homework, and I’m having trouble sleeping at night. My other TCK friends say it gets worse before it gets better. I’m just asking, does anyone have any coping mechanism suggestions?“

In another TCK community, it’s mentions of addictions to heroin and cocaine and self-harm that resonate most with others. One user admits that their identity feels so split between countries and cultures that they have no idea who they are. They say the only way to ease the pain from the sense of “split selves” is to cut themselves. This is the top-voted comment in response to a post about TCK struggles, a reflection of the deep resonance of that pain amongst those who were raised the same way.

Here is a truth laid bare: a TCK life is fundamentally disruptive. With disruption comes instability and loss, and when this occurs over and over again during one’s formative years, it creates layers of immense stress and unresolved grief. The harm burrows deep, often manifesting in extreme ways years and decades later.

What we also know now from dozens of studies: multiple moves during childhood correlate to poorer wellbeing later in life and leaves people more vulnerable to a host of problems, including identity issues, anxiety, depression, self-harm, suicidal ideation and attempts, higher mortality rates, etc. Let’s look at some of these studies and what they actually say.

A Sobering Reality Revealed By Data

Our likelihood of encountering serious issues later in life is influenced by the number of adverse childhood experiences (“ACE”) referenced in the previous essay. In a study involving 8,000+ people in the general population, researchers found that people who had experienced 4 or more ACE were 7.4 times more likely to develop alcoholism as adults than those with no ACE, and 3.7 times more likely to develop alcoholism than those with just 1 ACE.

Similarly, those with 4+ ACE were 10.3 times more likely to report injected drug use than those with zero ACE and 7.9 times more likely to do so than those with just 1 ACE. Moreover, those with 4+ ACE were 12.2 times more likely to attempt suicide as adults than those with zero ACE and 6.8 times to do so than those with 1 ACE (Felitti et al, 1998).

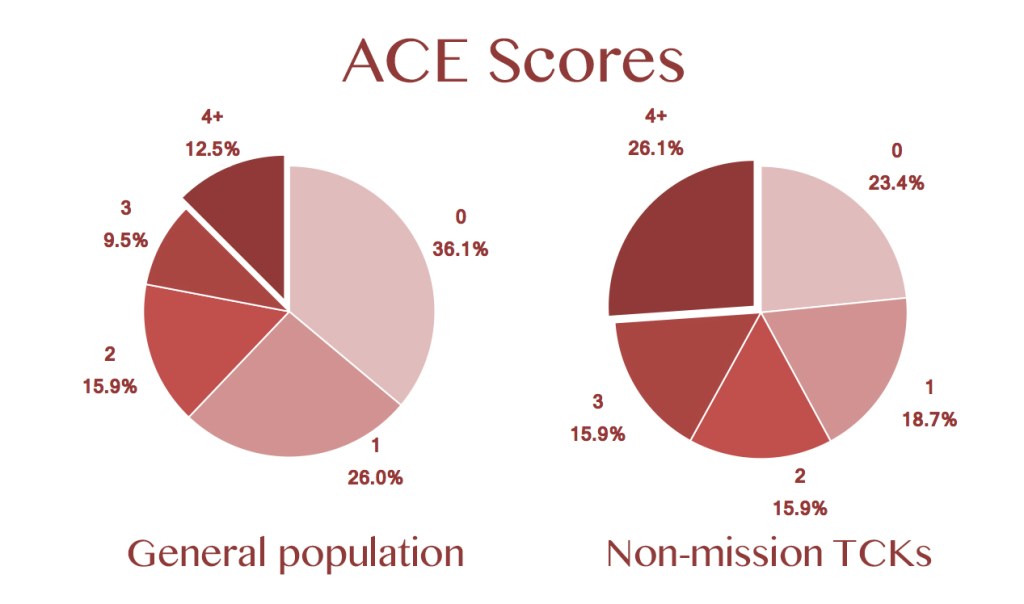

How do TCKs fare against the general population in the number of adverse childhood experiences? When comparing the CDC-Kaiser study of the general population (sample size: 17,000+) and the Crossman & Wells TCK study (sample size: 1,900+) referenced in the first essay, we know that a disproportionately large amount of TCKs experience 4+ ACE. The charts below summarise this disparity:

Where only 12.5% of the general population fall into the 4+ ACE category, some 26.1% of non-Mission TCKs fall into the same category. In other words, raising children as TCKs statistically more than doubles their chances of falling into a high risk category where the likelihood of alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicidal attempts in adulthood are much, much higher.

Shocking? Not at all if you are a TCK.

There are also some concerning findings for introverts in particular in a 10-year longitudinal study conducted in the US (sample size: 7,000+ people). Researchers found that the more times introverts moved as children, the more likely they were to report lower life satisfaction and poorer psychological wellbeing in adulthood. This was the case even when controlling for age, gender and education level. The study also found that introverts who moved more often as children had a higher rate of mortality and were more likely to die before they got to the second part of the study (conducted after 10 years), even when the data was controlled for age, gender and race (Oishi, Schimmack, 2010).

The researchers’ conjecture: for introverts in particular, frequent moves during childhood may have accumulated long-term stress reactions (eg. chronically elevated cortisol levels) which are known to be associated with mortality risk (Repetti et al., 2002; Sephton & Speigel, 2003).

A 2016 study conducted in Denmark (sample size: 1.5 million people) looked at the number of house moves one experienced before adulthood and incidents of psychosocial problems later in life. This study counted inter-municipality moves only and excluded moves within the same municipality, thereby excluding smaller, less disruptive moves such as moves to an adjacent neighbour that allowed the child to continue studies at the same school or city.

This study found that multiple relocations, particularly during early and mid-adolescence (ages 10-14), was linked to a higher likelihood of violent offenses and attempted suicides in adulthood. This was the case across all socioeconomic groups (Webb et al, 2016). The study also found a link between the number of relocations during adolescence and substance abuse and a higher rate of mortality in adulthood. And if these are the effects found in moving within a single country, how much more disruptive and damaging are international moves to different countries and cultures, as is the case for TCKs?

Whilst correlation does not always mean causation, suffice to say that the findings from these studies tangential to a TCK upbringing resonate deeply with many of us, even those like myself who enjoyed many aspects of a TCK life when growing up. We know that multiple moves across countries extract a price from the child because that is our lived experience.

In the future, it would be great to see more quantitative studies that look directly at the rate of anxiety, depression, etc. amongst TCKs compared to the general population, though the paucity of such studies today are understandable. There are two key reasons for this:

1) we tend to move a lot between countries so are often hard to track down for studies that run for years or decades;

2) our international nature makes it difficult to establish sufficiently large and suitable control groups for comparison, since cultural differences between countries could confound any findings.

A Litany of Questions

So why is it that the outcomes for TCKs in adulthood appear to be so extreme, with some TCKs appearing to be well-adjusted whilst some have to grapple with a host of psychosocial issues? And why do so many TCKs appear to be doing “just fine” as children, only to have severe issues develop later in adulthood?

As parents, are there specific ways to mitigate the challenges of a TCK upbringing so that our children are less likely to struggle with mental and physical issues years later? Happily, the answer is yes. But first, we need to address a toxic lie.

The Myth of the Resilient Child

“Children are resilient and adaptable”, so says conventional wisdom. There is an element of truth here in that children are not yet fully developed so are in some ways malleable. Yet when this idea is exported wholesale to raising a TCK, morphing into the rather naive but incredibly common parenting belief that “moving can be hard, but once the kids adjust they’ll be fine”, it becomes deeply problematic.

Unfortunately for many TCKs – myself included – this was precisely how we were raised. The decision to uproot the family from one country and move to another was often made on our behalf by our parents, with little to no consideration for how we actually felt about the matter.

“But sometimes that’s just how it is,” you might say. “Moving for work could be a necessity. What the children think won’t sway the decision.” My counter-argument: even if the move itself may be inflexible, it is possible to communicate with children in ways that make them feel heard and validated.

Uprooting everything and moving to a foreign country can be daunting enough for an adult – can you imagine what it feels like when this is forced upon you as a child, someone who does not yet have a developed, stable sense of identity and may still find the world they inhabit hard to understand at times?

Sometimes, we are simply told about the move mere weeks, days, or hours beforehand, compounding the element of shock and sense of instability on a young mind. Do that a few times throughout our formative years and no wonder such callous handling of big moves warps the children’s psyche, sowing the seeds for instability in the years and decades to come.

A Voice Unheard

Many TCKs can attest to a further challenge. If we tried to tell our parents how sad or anxious we felt about a move, our feelings were often dismissed. For some parents, it’s because as adults they find the idea of international exposure appealing and think that, by extension, it must be wonderful for children too. They then think that it’s the child who doesn’t know better and needs to “come around” to realising what joy and privilege it is to have an international upbringing. This, of course, is misguided thinking. Research in child psychology has shown that children need a safe and stable environment in which to figure out their own identity. Without this, they cannot explore boundaries as needed nor mature healthily.

As Harvard University’s Center for the Developing Child puts it:

“Children whose environment of relationships includes supportive caregivers, extended families, or friends who are not overly burdened by excessive stress themselves can be protected from potential harm and develop the building blocks of resilience that lead to healthier and more productive lives.”

Look at how many components of a healthy life are often missing for a TCK here. When a parent dismisses a child’s feelings on a major life event like an international move, the “supportive caregiver” element is gone. And by moving out of a country, the child is losing their connection to extended family and/or friends – a critical element of a safe and stable world for the child. A foreign environment also puts the child under stress for temporary or extended periods of time. If the child fails to truly adapt to their new life, they are often missing virtually all of the building blocks for a healthier, more productive life.

A Question of Ability

Other times, the children’s feelings are dismissed because the parents themselves also harbour some anxiety about the move. Denying the child’s negative feelings is, sadly, a convenient way for the parents to avoid dealing with their own qualms.

What’s more, communications between adult and child can be hard because children aren’t yet mature enough to express themselves eloquently, and their torrent of emotions may come out in awkward ways that require more empathy and patience from the parents to decode. Unfortunately, not every parent possesses the emotional capacity and maturity to properly listen to their child in their time of need.

The Guilt Trip Before the Plane Trip

To make matters even worse, when a child tries to share their anxieties many parents of TCKs would rush to emphasise the positives of the move instead (“You are so lucky to be able to travel and see the world!”/“You should be grateful for the opportunities that others don’t have”). Yet this ardent emphasis on the positive is often detrimental.

The children are often made to feel guilty for feeling the way they do and are shamed into thinking that they themselves and their emotions are the problem. Sometimes, the parents’ refusal to acknowledge the anxieties surrounding a move can also engender frustration, mistrust, and a deeper sense of isolation in the child.

Silence As A Form of Self-Defense

Whether out of hubris or well-intended (but misguided) thinking, when it comes to moving countries many parents ultimately believe that they know best, that a child can’t possibly understand what’s good for themselves, and so rarely take the time and energy needed to listen – truly listen – to what their children have to say.

Over time, when multiple attempts at communications with parents fail, and when the world at large is eager to heap praise on your “wonderful life” and is blind to the problems that come with it, children resort to self-censoring. After all, what’s the point of saying anything? Your viewpoints would just be dismissed again. Worse yet, you could get branded as an entitled, ungrateful child by everyone.

Another reason for children to self-censor: dependency. When our family leaves a country, we lose all that is familiar to us within the space of a single flight – the people, the culture, the routine. The last thing we need right then is strife with our parents/immediate family – the only constant figures in our lives when everything else has changed. So, in an effort to keep the peace with those on whom we are now heavily dependent, some of us just opt for silence.

Battles on Other Fronts

Besides, as TCKs we’re often too busy to complain because we have other things to worry about. When a big move happens, TCKs go into survival mode. There’s a whole new set of cultural rules to learn and adapt to, social dynamics at the new school to figure out, a need to make friends and find our footing in our new life, etc. We need to figure out all of this ASAP. Our sense of self and belonging depend on it.

The problem: understanding a culture is a lot harder than it seems. How hard exactly?

The Cultural Iceberg

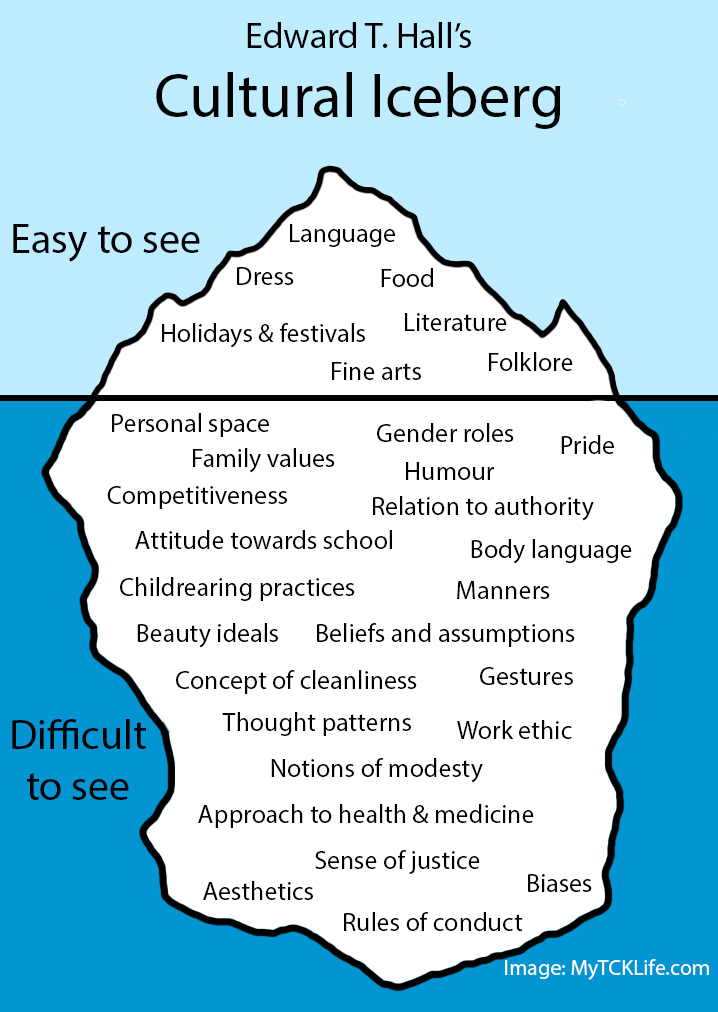

In 1976, anthropologist Edward T. Hall developed a concept to illustrate the many complex elements that make up a culture. He called it “the cultural iceberg”.

There are aspects of culture that are easy to see: what we eat, how we dress, what language(s) we speak, etc. Yet these are only a fraction of what makes up a culture.

To truly feel at home in a community, we also need to grasp the subtle, less apparent elements of a culture, many of which vary greatly from country to country: body language, gender roles, type of humour, competitiveness, rules of conduct, approach to health and medicine, notions of modesty, biases, concept of justice, manners, beauty ideals, core values, to name a few.

Grasping all or even some of these subtle elements of culture is a tall order for an adult. It can be the work of years. Yet with a single move, a child is essentially asked to give up all that they know of one culture, and to make space in their head and heart to understand and embrace the intricacies of another cultural iceberg. Failure to do this means the child will struggle to feel a sense of belonging, that all-important state of mind that grounds us. But here’s the catch: you cannot quite understand a culture without first suppressing a part of yourself to some degree, because we learn about others by observing, not by imposing ourselves upon another culture.

And so as TCKs we learn to self-censor – we suppress our true feelings in front of people who do not want to hear about the complexities of a TCK life; we suppress who we are every time we arrive at a new host country. But suppressing our emotions and our identity will only delay the important work of emotional development and identity formation. This results in what psychologists call “delayed adolescence”, an extremely common TCK problem that warrants an essay of its own.

Ultimately, all this self-censorship adds more layers of stress on the psyche. Yet from the parents’ perspective, everything seems great because they can point to the uncomplaining child and say, “See? Now that she’s adjusted, she’s doing just fine.” And so, the terrible myth of the resilient child perpetuates.

The Curse of Social Media

Some may think that being a TCK today is easier than before. Social media, after all, is meant to help people stay connected. Unfortunately, social media is every bit the double edged sword for TCKs as it is for everyone else. Ample research has shown that extensive exposure to social media is linked to a greater sense of loneliness and higher rates of anxiety and depression. The constant stream of curated posts, of everyone eager to showcase their best selves, skews our perception of reality. It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking our own lives are worse than our friends’.

And whilst technology can in theory help us stay better connected, our ability to stay in touch with friends depends ultimately on both parties wanting and able to stay in touch. Yet as all TCKs have learned, when you move away from a place, the people of that place also move on from you. Their lives carry on as normal, and nothing quite drives this home like social media. Here’re a sample of what TCKs have to say (republished here with permission):

“I moved 3 years ago and now I watch my friends’ Instagrams as they go on school trips and I cry every time I see their stories. I miss them. They don’t miss me. They don’t even wish me happy birthday but I remember all their birthdays.“

“Social media is a big thing and I just see old friends hanging out and I know I’ll be hanging out with them if I hadn’t moved. I’m really sad because now I’m having trouble getting friends when the ones who understand me the most are right in my phone but now as days pass we drift farther and farther and I’m just getting lonelier.”

Human Nature Found in Mother Nature

In the field of botany, there is a phenomenon that mirrors what happens to humans in the face of repeated disruption. When young saplings are taken out of the soil repeatedly then transplanted again and again, they often develop a defensive root system. Instead of sending deep anchor roots down into the soil, they tend to develop more fibrous, shallow root systems that spread horizontally. Whilst this alternative root system has some advantages like allowing the plant to take up nutrition and water more quickly, it also leaves the plant more structurally unstable and more likely to die whenever adverse conditions like droughts arise.

Interestingly, some plants never fully recover their natural root growth patterns even after being permanently planted. They maintain this defensive, shallow root system as a lasting adaptation to their early experiences, a similar problem that confound many TCKs today.

How Do We Do Better As Parents?

I believe that many parents genuinely want the best for their children. This is why there’s such enthusiasm for the TCK way of life: the benefits of an international upbringing seem so clear. Yet as we consider this path, we must also ask ourselves: do we truly understand the price of this path and what it is that we are taking away from our children? Do we understand that resilience is more a myth and a coping mechanism, and that the damage of a TCK life on children can sometimes be profound and permanent?

Having looked at some of the bigger problems and vulnerabilities that a child is exposed to as a TCK, the obvious question is: how do we as parents do better?

In my next article, we’ll look at three key frameworks in which to think about solutions and the fundamental ingredients for a TCK to succeed. We’ll also dive into some real life success cases and hear what they have to say about their upbringing. If you want to stay posted and be notified when the next essay is out, please subscribe below. Meanwhile, I’d love to hear from you in the comments section.

21 responses to “The Myth of the Resilient (Third Culture) Kid”

As both an international school teacher and parent of a TCK child, I feel compelled to share a different perspective on this thoughtful article. While you raise important concerns about the challenges and potential long-term impacts of the TCK experience, I’ve observed a more nuanced reality through my years in the classroom and at home.

I taught in Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, China and Thailand.

In my daily interactions with hundreds of TCK students, I witnessed remarkable joy, resilience, and genuine happiness that seems understated in your analysis. These weren’t just surface-level observations – as a teacher, you develop a special ability to recognize authentic well-being in your students versus coping mechanisms.

That said, your article has made me reflect more deeply on what might lie beneath the positive experiences I observed. Perhaps some students were indeed masking deeper struggles, as you suggest. Your insights about delayed impacts and the “myth of resilience” are particularly thought-provoking, especially as I consider my own child’s past journey through the international school system.

The real truth may lie somewhere in between – acknowledging both the very real challenges you’ve outlined while also recognizing that with proper support systems, engaged teachers, and aware parents, many TCKs can and do thrive. Your article serves as an important reminder that we shouldn’t take apparent resilience for granted, and that we must remain vigilant in supporting these children’s complex emotional needs, even when they appear to be flourishing.

I particularly appreciate your call for better parent-child communication around international moves. Even when circumstances necessitate changes, we can certainly do better at acknowledging and validating our children’s feelings throughout the process.

Thank you for this thought-provoking piece. It has encouraged me to look beyond the surface happiness I observed in my classroom and consider how we might better support TCKs’ long-term emotional well-being.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your thoughtful feedback! It’s always a pleasure to hear from educators who have experience with TCKs. My starting point for this essay was to try to capture both ends of the spectrum in terms of outcomes – because it’s true that some TCKs seem to thrive later in life whilst others struggle. It is the former that the world seems eager to laud and embrace, and the latter and their issues that unfortunately get so little acknowledgement/air time. My hope for the article was to adjust that imbalance in perception of what a TCK life actually looks like – backed by data and research, of course. And once I started researching, it dawned on me what a gilded life I had, and how many of the worst consequences I’d managed to dodge.

So to be clear, I’m not positing that TCKs are doomed, but that the likelihood of long-term adverse outcomes are higher than most people realise and therefore we need to be extra careful about the potential pitfalls if we need to/choose to pursue a TCK path for our children.

You mentioned that you taught at international schools and had occasion to observe many genuine instances of joy/positivity. In the 2021 TCK study by Crossman & Wells, they found (see White Paper #1 and #2 on their TCKTraining.com site) that it was the TCKs who went to local schools (VS those who went to international schools) who struggled more and experienced more ACE (adverse childhood experiences). So I wonder if part of your perception may have to do with the fact that your experience within an international school setting (where children tend to come from wealthier/more educated families) showed a certain subset of TCKs, but not the experience of other, less-privileged TCKs.

I would also add that I enjoyed large chunks of my TCK experience during childhood/adolescence, and an observer would look at kid/teenager-me and say “there’s a happy, well-adjusted child”. Yet there were actually issues brewing even then, but they were so well concealed that it took 2 more decades (until I was in my 30s) for me to realise that some of my deep-seated flaws have a lot to do with my TCK upbringing.

Perhaps that is the value of the longitudinal studies cited here involving thousands to over million people – it shows us a more accurate and longer-term picture that no one can be reasonably be expected to understand over the span of even a multi-decade career as a teacher.

I’m excited to share the next essay, as I’ll be diving into some key factors that influence long-term outcomes for TCKs. Hopefully that piece would give us more reason to be optimistic 🙂

Again, thank you for such a thoughtful comment, and I hope to re-connect with you at another point in time!

LikeLike

This discussion regarding international schools is interesting and made me reflect on how my TCK life unfolded. I went to a local school in a conservative, rural district for the first few years of my family’s move, where I was miserable and constantly complaining about the ignorance and bigotry of my teachers and peers. Eventually I transferred to a school with a large number of international students and formed a friend group made up of other internationals, TCKs, and second-gens, and I felt so much happier and more accepted. I do think international schools can significantly improve the TCK experience, as it is easier to feel integrated in your community when everyone around you also feels like an outsider.

LikeLike

I await the next essay. I am a third culture kid, M.K., and my oldest son, an introvert, is a Fourth Culture Kid.

LikeLike

Thank you for this article. It resonates so much and gives me comfort to know I am not the only one.

I am a 36 year old TCK and have only just recently been diagnosed with anxiety, depression (including post partum), eating disorder and body dysmorphia although in hindsight probably in majority due to the TCK lifestyle.

LikeLike

What an awesome, well-written article. Shortly after my family moved to a new country when I was 7 years old, I was crying to my mom about how much I missed my home country and my family. She replied something along the lines of, “Well, what do you want me to do about it? It’s not like we’re going to move back.” I always reflect back on this moment as a perfect example of what was wrong with my TCK experience: my emotions weren’t validated. Your article expressed the importance of validating the TCK’s emotions very well. I hope it is able to reach more parents and teachers of TCKs to help them realize how vital it is.

LikeLike

I relate to so much of this. The self-censorship. Having my feelings dismissed by my parents and being told I should be grateful. Moving away and watching from afar as my friends moved on and forgot me. Being expected to make a new home in a culture I never fully understood or fit into. Relying on my parents for social interaction and familiarity, while knowing they were the reason I was lonely.

As a child, I knew how it made me feel. But as an adult, it’s easier to see what it actually *did* to me in the long-term.

For parents, I think validating your child’s feelings about this situation is SO important. No arguing, no “but you’re so lucky!” Just listen and acknowledge that their feelings are normal and valid.

The first time an adult in my life took my feelings about this seriously, it was life-changing. But it shouldn’t have been. It should have been the norm.

Thank you for this well-written and well-researched article.

LikeLike

I’ve read and thought a lot about being a TCK, so nothing here is *really* new to me, and yet you put things together in a way that still brings me new clarity. It’s like individual puzzle pieces being arranged in a way that makes so much sense – and you ground it in research, which I really appreciate.

This time my biggest takeaway is the term self-censorship. I’m recognizing that self-censorship was indeed a key theme of my TCK childhood as the child of emotionally immature parents (the source of my ACEs), and it’s been a theme in my marriage, too. I’m 33 now and only just fully stepping into my right to not censor myself and make decisions for my own life instead of absorbing others’ worlds.

Thank you so much. This was very healing.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for this article. It feels so nice, even therapeutic, to be understood by someone. I used to suffer from depression for years and I have been constantly told by my family that I’m spoiled, weak and ungrateful because I felt what you describe in this article. Despite the fact that the move was really hard. My parents moved with me to a very conservative, reserved country when I was 13. I was bullied at school, the teachers used to tell me they don’t want to teach me and I should go back to my home country (I wish I could!). Even strangers sometimes used to yell at me that they don’t want me in their country. It ruined my education, my self esteem, my mental and physical health (I developed insomnia which I was never able to get rid of). Despite all of this, my parents never showed regret or even understanding for what I was going through, the only thing they cared about were their careers.

Today as an almost 30 year old, I have a great life. I moved back to the town where I was born, found a wonderful man and got married. However, one thing I still struggle with is anger on my parents and not being able to forgive them. Not for moving me, but for ignoring me and shouting me down when I asked for help. For telling me I don’t deserve to have a normal childhood with friends and extended family. I have never been able to trust them ever since and even though I know they love me and I try to call and visit them as much as possible, I feel like my trust is gone forever. I’m curious on your and other TCKs experience and thoughts on this. I would love to feel close to my parents but I haven’t been able to resolve this. I hope I will be able one day. I really love them and want to be with them fully, not half hearted like now. Do you have an advice for me?

LikeLike

Hi! I’m so glad to hear that you managed to overcome most of those terrible experiences in your childhood and now have a great life as an adult! Regarding your question on how to resolve the relationship issue with your parents, a lot of that resonates because I, too, have parents that I can no longer trust. I have found my own resolution to my situation but my first questions to you are: have you tried bringing this up to them in recent years? To tell them how their dismissive attitude towards you was deeply hurtful and that you still have unresolved anger from this? If so, how did they respond? Unless you can communicate with them frankly about this, I don’t think you’d be able to resolve your trust issues, nor would you be able to find a resolution that you are happy with.

I do feel that I have more advice on this front, but it would really depend on your answers to the questions above.

Big hugs to you.

LikeLike

Beyond the topics others have raised, I’d like to mention that TCK life is something that provides significant cover for abusers. In my case, one of my parents decided our clashing personalities was reason to take me to a bogus “attachment therapist” who recommended moving me to a different country and cutting off all my relationships.

According to the therapist this would force me to “bond” with her since I would be deprived of all other connections. Needless to say that didn’t work and we have been no contact for decades.

This may not be the most common situation among TCKs but I suspect I am not the only one whose parents used constant international moves as a cover for severe abuse.

LikeLike

You raise an excellent point!! I’d come across a similar point during my research for this TCK series. Though I can’t quite recall the source, it was mentioned that a lot of TCKs experience abuse and/or neglect below the radar because TCKs get moved around so much. This makes it difficult for professionals within their support network (eg. teachers, counsellors, therapists) to keep track of us and be able to genuinely assess our wellbeing. Also, because of our short stints everywhere, all that these professionals have are a snapshot of us in a relatively short space of time. Without fuller context, it’s very difficult for them to establish a baseline and to be able to assess who we are and how we have been affected by certain circumstances/changes in our lives.

My heart goes out to you and what you’ve been through.

LikeLike

Great articles! Could have also been interesting to explore the reasons why the TCK experience increased the incidence of the ACE factors of emotional abuse, HH mental illness, and emotional neglect. If I had to guess, the lack of support during the loss/grieving (leaving) and anxiety (arriving) acts as a mediator to the ACE factors. The emotional invalidation, gaslighting, and lack of acknowledgement of the loss from our parents and institutions/schools for example. The pain of not being seen, heard, and supported. Another mediator could be the lack of awareness and psychoeducation around what it means to be a TCK. I also don’t think the ACE scores fully capture the real risk factors of the TCK experience. I wonder what my childhood would have looked like if I was introduced to the concept of TCK early on and built a community and sense of belonging around other kids that also identified as TCKs

LikeLike

I’m a former TCK and current parent. Without trying to start conflict, I’d like to push back on this idea that seeing kids happy at certain moments means the article is overly negative or lacking in nuance. These do not mean a teacher is able to fully grasp a child’s perspective or experience. I’m sure some of my teachers would have said the same for me, and TCK life had an almost wholly negative impact on my childhood.

It’s my view that TCK life is a developmental injury of sorts. It may have benefits in some cases, although I do not think these are as significant as claimed. But even though the negative aspects are cushioned in some cases, they are a real and unavoidable part of TCK life.

Children and adults have different needs. Of the two, children’s best interests should take precedence in all situations. Parents should recognize that what they want – adventure, travel, novelty – should not come before their children’s basic developmental needs to have stability, familiarity, and consistent relationships.

Children are not young for very long and developmental tasks can’t be put off for later. Those undertaking the work of parenthood need to put their kids’ developmental needs over their wants. To do otherwise is very selfish, and I must be honest, I think that is a fair description of some parents choosing this lifestyle.

I think many TCK parents are reluctant to acknowledge that their choices may be damaging, which indicates to me that at some level, some do realize it. I see a lot of defensiveness in parent groups regarding this. There are a lot of recommendations for how to mitigate the impacts of TCK life – mostly therapists, social clubs, etc.

Rarely do I see it mentioned that perhaps, parents seeking this out should reconsider disrupting their children’s lives like this. Securing some sessions with a therapist isn’t a get out of jail free card.

I don’t want to condemn people for choosing TCK life for their families. Not everyone has a choice after all, and in some cases, TCKs grow up to feel their upbringing was beneficial. But the costs are real, and in many cases far outweigh any benefits.

I do think that parents choosing this for their kids need to be honest with themselves and understand while it comes with benefits for them, it *will* have costs for their children. And perhaps later for parents. While it wasn’t the only reason, my parents’ selfishness in choosing this lifestyle, and continuing it after seeing that it had negative impacts on their kids, was part of the reason I am no contact with them today.

LikeLike

Hello –

Sometimes I think I’m the odd one out of the TCK community.

I truly appreciate the lifestyle that my parents gave us, I feel it a privilege to have lived in the places we did.

Every time I read or am told of the sadness /disconnection / depression/etc that many TCKs have, I’m just flabbergasted. I must be the lucky one.

I think the only problem we have (my older sister too, not so much my younger one), are the raised eyebrows and looks of disbelief we get when we tell our stories of growing up, so we have learnt to not be quite so forthcoming with those tales.

I’m Danish, born in Ghana, and was lucky enough to spend my childhood in Denmark, Pakistan, Tanzania, Kenya, Lesotho and South Africa. I chose to stay on in South Africa, and I often get other TCKs, now living back in their countries of origin, being envious that I still live in a faraway country.

Funnily enough my daughter, who is South African born and bred, considers herself a TCK, as she feels she was brought up in a more Danish and than an SA household, and now flits between SA and Ireland, the country of her father’s forefathers.

LikeLike

Hi, I would like to share this article on my website and ask for permission to do so. http://www.LittleNomadsCoaching.com

LikeLike

Hi Jessica, yes that’s fine but please don’t export/re-publish the entire essay. Feel free to quote small sections and link back to this original article if anyone would like to read it in its entirety. Thank you.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this article! It touched on so many things that I often try to explain to people but only my other TCK friends ever get it. I may be brilliant at making friends quickly and bonding but like the article said, I am always repressing different parts of myself. I am built of so many different cultures that I often feel like I’m lying about my identity because I shove some parts down unintentionally. I love the experiences I’ve had but sometimes I wish I grew up “normal.”

LikeLike

[…] Peng, J. [EverywhereNowhere852]. (2025, January 19). The myth of the resilient (third culture) kid [infographic]. https://mytcklife.com/2025/01/19/the-myth-of-the-resilient-third-culture-kid/ […]

LikeLike

[…] Note: Following the publication of my 2nd essay, which details many longitudinal studies that found elevated risks of a host of adverse outcomes […]

LikeLike

Sehr interessanter Artikel, der viele tiefgreifende Aspekte der TCK-Erfahrung beleuchtet, insbesondere die langfristigen psychologischen Auswirkungen. Die Diskussion über Resilienz als Mythos und die Bedeutung der Validierung von Kindergefühlen ist entscheidend. Ich frage mich, wie man diese Erkenntnisse in die tägliche Erziehungspraxis integrieren kann, insbesondere für Eltern, die möglicherweise internationale Umzüge in Betracht ziehen. Gibt es spezifische, praktische Rahmenwerke oder Ressourcen, die Eltern helfen können, die emotionalen Bedürfnisse ihrer Kinder besser zu unterstützen, anstatt sich auf das Konzept der “Resilienz” zu verlassen? Ich bin auf einen Leitfaden gestoßen, der sich mit der Förderung von Widerstandsfähigkeit aus einer inneren Perspektive befasst – vielleicht sind einige der dortigen Ansätze anwendbar: https://wecec.net/raising-a-resilient-child-a-guide-from-the-inside. Hat jemand ähnliche Ressourcen oder Erfahrungen mit solchen Ansätzen?

LikeLike